Homegrown ‘The Velocity of Autumn’ goes from Broadway to community theater

Story by Bob Abelman

“I admit,” confesses Cleveland Heights resident and prolific playwright Eric Coble, “that it became one of my goals, many years ago, to have a show successful enough that a local community theater would do it, without my involvement, not knowing anyone there, as if they were doing a show by any other national playwright. Then, I’d feel I’d arrived.”

And now he has.

Coble’s “The Velocity of Autumn,” the final installment of a trilogy of plays about one woman at vastly different stages of her life, made its Broadway debut in 2014 at the Venetian Renaissance-style Booth Theatre on West 45th Street.

The play addresses the struggle over autonomy we will all face and the conversation we will all have with our loved ones in the years of our decline. True to Coble’s signature sardonic sense of humor, “The Velocity of Autumn” opens to find Alexandra – played in New York by 86-year-old Oscar-winning and Tony Award-nominated Estelle Parsons – self-barricaded in her Brooklyn brownstone surrounded by enough Molotov cocktails to take out the neighborhood so that her estranged children can’t ship her off to a nursing home.

And now “The Velocity of Autumn” has come home, having just completed seven highly successful performances at the Chagrin Valley Little Theatre.

The CVLT, located just off the charming early 19th century town square in Chagrin Falls, is one of the oldest, continuously operating community theaters in the nation and the beneficiary of local pride imbued with a touch of hyperbole. On the street that houses the unassuming red brick CVLT mainstage and the even less assuming 65-seat former storage space where Coble’s play was performed is a sign that boasts the presence of a “Theatre District.”

About community theater

It is this quaint civic conceit and a propensity for producing chestnuts written during the Hoover administration that have made community theater an easy target for on-stage satire. Look no further than Michael Frayn’s “Noises Off,” Alan Ayckbourn’s “A Chorus of Disapproval” and Henry Lewis, Henry Shields and Jonathan Sayer’s “The Play That Goes Wrong,” among others.

Christopher Guest’s now-iconic mockumentary “Waiting for Guffman” is the poster child for using community theater as a punch line and occasional punching bag. Even the reviews of this 1997 film skewer the plays and the amateur players in them.

“(The film) will ring true with anyone who’s ever acted in a community theater production, or worse, had to sit through one,” wrote CNN’s Mark Scheerer.

“Community theater can be a very dark thing. Think about it: The dreams of the bright lights of Broadway and one’s face beaming on the front of a playbill replaced by high school auditoriums and a misspelled mention in the local newspaper,” wrote New York Magazine’s Eliot Glazer.

Amateur theater has been around since Colonial and Revolutionary War times. But what is now known as “community theater” – a term coined in 1917 – sprang up from The Little Theater Movement of that era. It began as a web of amateur theater activities undertaken across much of the United States between 1912 and 1925 that opposed commercialism in the arts. Its proponents believed theater done locally could be used for the betterment of and self-expression by small communities.

These troupes performed in found spaces, such as churches, halls or stables, and were supported by local subscription, which meant they had very small budgets and limited production values. The CVLT did its first productions in the Federated Church gym, and later, in the upper floor of the Old Town Hall a block from the theater’s current location.

There were more than 500 volunteer-based community theaters by the end of the 1930s, the number rising tenfold in the subsequent three decades. The American Theater Association served as a central body for these theaters, which noted that part of the problem in counting community theaters was their unnerving propensity for “multiplying like rabbits and dying off like fruit-flies.”

Today, the American Association of Community Theaters believes there are more community theaters (7,000 across the United States and its territories), involving more participants (about 1.5 million volunteers), presenting more performances of more productions (more than 46,000 productions per year), and playing to more people (approximately 86 million annually) than any other performing art in the country.

Locally, the Ohio Community Theatre Association serves more than 100 member theaters across the state and some 22 community theaters in the northeast region, which includes Ashland, Ashtabula, Columbiana, Cuyahoga, Geauga, Holmes, Lake, Lorain, Mahoning, Medina, Portage, Stark, Summit, Trumbull and Wayne counties. The CVLT is one.

The CVLT steps up

Rollin Devere, longtime actor with the CVLT and current head of its play selection committee, is all too aware that good contemporary plays rarely make it to the community theater stage in a timely fashion. They get quickly swept up by local professional companies that have priority when it comes to production rights.

“But ‘The Velocity of Autumn’ was performed by the Beck Center for the Arts (a professional company in Lakewood) before it went to Broadway,” he notes, and it is slotted for a professional production at Cleveland’s Karamu House in March of 2019. “So, we were able to jump in and secure the rights.”

To date, there have been 36 other nonprofessional productions of “The Velocity of Autumn” performed across all regions of the country.

The script came to the CVLT’s play selection committee’s attention by way of director Kate Tonti, who pitched the show as one she would like to take on even though she had never seen it performed.

What inspired Tonti’s enthusiasm for the work and resulted in the 13-member committee’s unanimous approval of it – “which rarely happens,” adds Devere – is the small cast, simple staging, relevant subject matter, Broadway pedigree and the play’s local authorship.

“I’ve done many, many shows,” notes Tonti, “but never when the playwright said he was available to see the production. This is very exciting and a bit unnerving.”

And there is a hint of apprehension that, like the famous New York producer who was expected to attend an opening night community theater performance in the film “Waiting for Guffman” but did not, Coble might be a no-show for this one.

The playwright’s perspective

But Coble wouldn’t miss this opening night for the world, and like Tonti, found the experience both exciting and unnerving.

“I can never relax watching my own plays being performed,” he said while sitting in the second row of the theater waiting for “The Velocity of Autumn” to begin. “Not in rehearsals, not in previews and not in performance. I am always judging lines, watching the acting choices, seeing the direction … I am always having a conversation in my head during a production about the production. This happens when I am watching any play, actually. Occupational hazard.”

There are, however, the occasional moments when a performance is so engaging that Coble manages to get sucked into the story and lost in the storytelling.

“And that happened tonight,” he said after the production. “It happened often. I was as close to actually enjoying myself during one of my plays as I can recall, aided by the fact that I had nothing whatsoever to do with getting the play staged.”

The aforementioned playwright, Alan Ayckbourn, sat through his fair share of community theater productions of his own plays, noting in a recent article in The Guardian, “It’s like a mother watching her newborn being strangled.”

“Not for me,” says Coble. “It’s special watching an audience – any audience – respond to my work.”

Rajiv Joseph (“Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo”), another local playwright whose work has gone to Broadway, recalls the advice delivered in a class taught by famed playwright Edward Albee about maintaining control of a play once it is published and goes public: “Be as explicit with instructions for delivering lines as possible.”

Coble doesn’t agree and sides with Shakespeare, who was notorious for an absence of stage directions written into his plays. “I have to trust actors, directors and designers with the script. They have to own the work. If I’ve done my job right in the writing, what I intended will end up on stage.”

“This is a collaborative process,” he adds, noting that a sense of a creative community is what defines community theater.

When reminded that the top ticket price for “The Velocity of Autumn” on Broadway was $173 while $13 gets you into the CVLT production, Coble attributes the escalated price to the privilege of seeing two award-winning actors performing in a lavish theater with elaborate production values and impressive ushers.

“But if the bang you want to get from your buck is seeing a production where the actors find the truth in their characters and in the play,” he says, “then the CVLT production was quite the bargain.”

The day the show announced its closing on Broadway, Coble posted on Facebook that he was “feeling damned lucky. What a ride.” After seeing the show done in his own backyard, he had a similar takeaway.

“I still feel damned lucky,” he says, “and the ride, most remarkably, continues.” CV

On stage

“The Velocity of Autumn” will be performed from March 28 to April 21, 2019, in the Arena Theatre at Karamu in Cleveland’s Fairfax neighborhood. For more, visit karamuhouse.org.

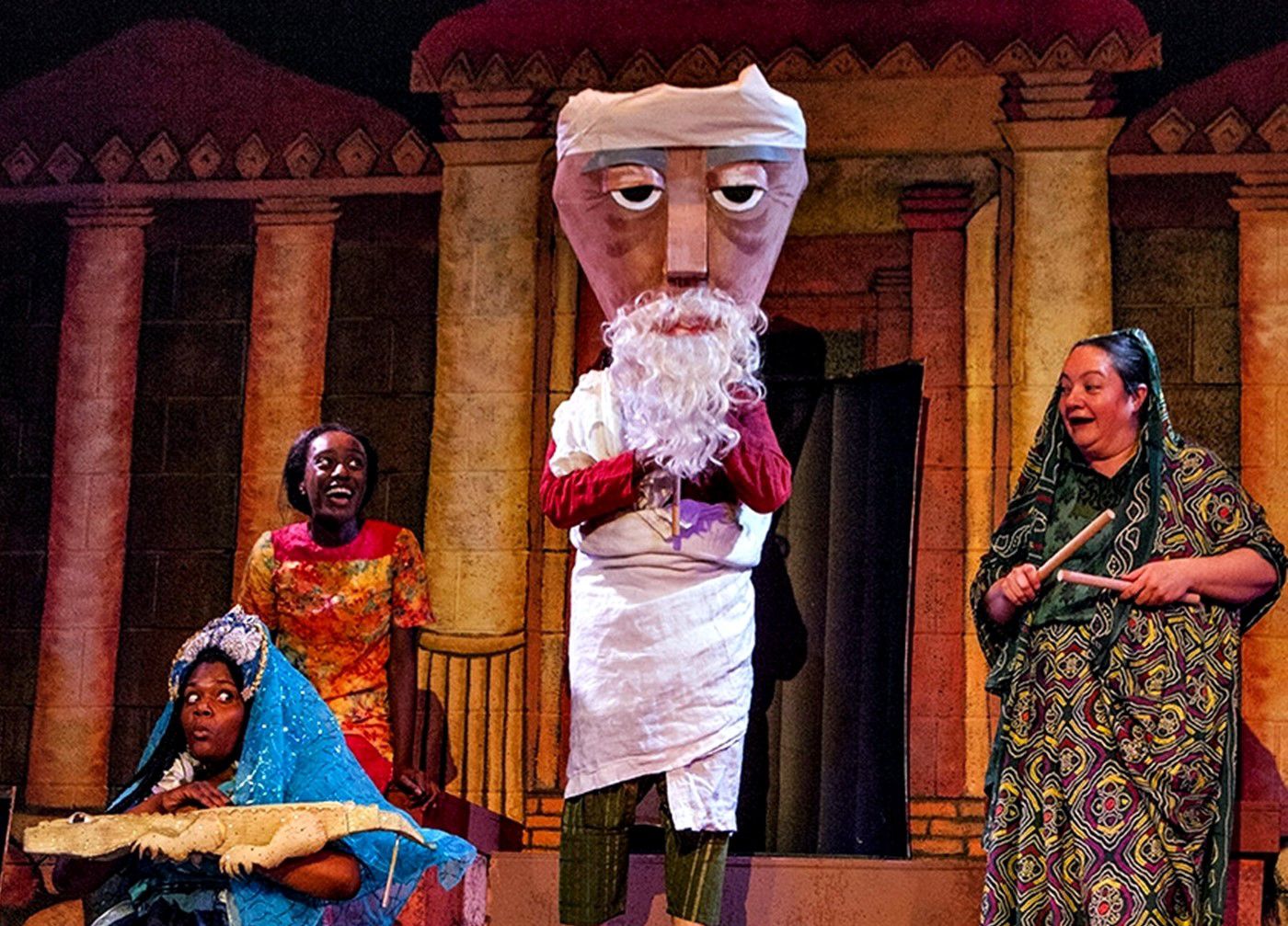

Lead image: Eric Coble in attendance at the Chagrin Valley Little Theatre opening night of “The Velocity of Autumn.” Photo by AJ Abelman Photography.

Ohio Community Theatre Association members

- Aurora Community Theatre, Aurora

- Brecksville Theatre on the Square, Brecksville

- Broadview Heights Spotlights, Broadview Heights

- Brunswick Alumni Community Theatre, Brunswick

- Canal Fulton Players, Canal Fulton

- Carnation City Players, Alliance

- Chagrin Valley Little Theatre, Chagrin Falls

- Dynamics Community Theatre, Tallmadge

- Hudson Players Guild, Inc., Hudson

- Medina County Show Biz Company, Medina

- Old Towne Hall Theatre, Inc., North Ridgeville

- Orrville Community Theatre, Orrville

- Strongsville Community Theatre, Strongsville

- The Wadsworth Footlighters, Wadsworth

- Theatre 8:15, Green

- Trumbull New Theatre, Niles

- Twinsburg Community Theatre, Twinsburg

- Wayne County Performing Arts Council, Wooster

- Western Reserve Playhouse, Bath

- Wolf Creek Players, Norton

- Workshop Players, Amherst