By Michael C. Butz

World-renowned photographer Ruddy Roye documents his subjects – often strangers – in much the same way he meets them in person.

His first shots are often wide, allowing the personality of surrounding buildings and streets to provide context. Then, he moves closer, snapping an image of his subject from the waist up. The interaction is completed when he takes a photo of only the person’s face. He adjusts the aperture of his 50mm Noctilux lens so that all that’s in focus are the subject’s eyes.

“It’s a way of introducing viewers to the person. … And for me to say, ‘Look, look at who a Clevelander is,’” says the 49-year-old Jamaican-born, Brooklyn, N.Y.-based artist. “I want you to be engaged with this person and to ask questions – and to get answers from that face.”

That approach is particularly relevant for his current project, “Cleveland 20/20: A Photographic Exploration of Cleveland,” in which he’s one of more than 20 photographers documenting Cleveland and its residents. Roye is the only non-Clevelander among this veritable who’s who of Northeast Ohio’s artistic photographers.

“The project has many folds. One of them is to photograph the most diverse, segregated city on this continent,” he says. “How do I do that? I stay as an outsider, using fresh eyes – sometimes ignoring the history just to get to what is there.”

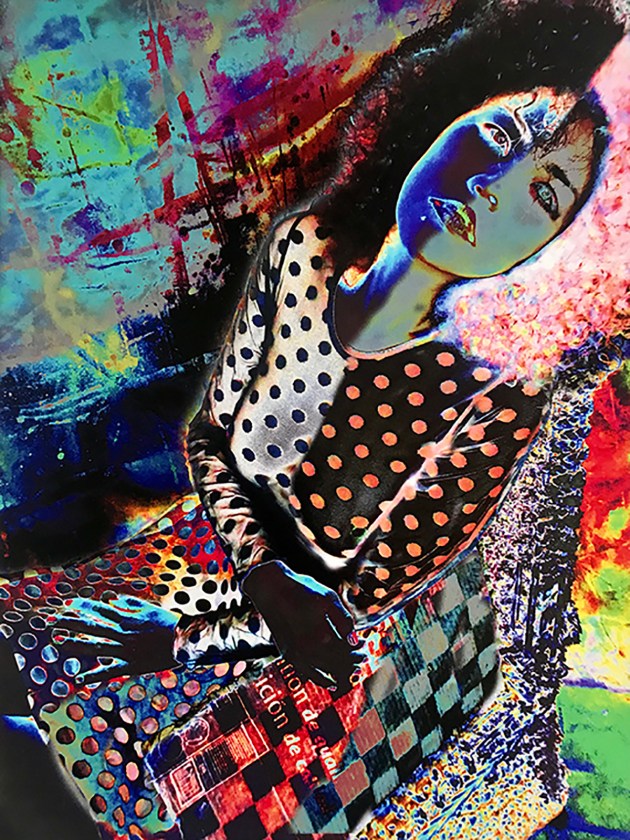

neighborhoods. Image courtesy of Cleveland Public Library Archives.

Connecting to Cleveland

“Cleveland 20/20” is a partnership between the Cleveland Public Library and Cleveland Print Room. To mark its 150th anniversary, the library sought to document the diversity and richness of everyday life in its hometown. Between “Cleveland 20/20” and a similar partnership with ideastream on a storytelling project, a comprehensive portrait of the city will emerge.

The photos compiled for “Cleveland 20/20” will be cataloged in the library’s Photographs Collection, which currently holds 1.3 million photographs, most from the mid-1800s to the 1990s. Thus, this project will provide a needed update. Secondly, a portion of the “Cleveland 20/20” photos will appear in a major exhibition scheduled to open Jan. 20, 2020 in Brett Hall at the library’s main branch in downtown Cleveland. It figures to make a splash.

Cleveland Print Room Executive Director Shari Wilkins says “Cleveland 20/20” got started in October 2018 when Aaron Mason, the library’s director of outreach and programming services, reached out to her with his vision for the project.

“He wanted a number of local photographers, and then also asked about hiring an outside photographer,” she says. “We’d already worked with Ruddy two times, basically, so it was a no-brainer.”

In 2018, Roye was an artist-in-residence for Cleveland Print Room’s Project Snapshot program, which through a partnership with the Ohio Civil Rights Commission aims to teach photography to area young people. In 2019, Roye’s much-anticipated solo show, “When Living is a Protest,” debuted at Cleveland Print Room.

Also on Roye’s resume: TIME Magazine named him Instagram Photographer of 2016, and he’s worked for the likes of National Geographic, TIME, The New York Times, Vogue, Jet, Ebony, ESPN and Essence.

Though he acknowledges similarities between his “When Living is a Protest” series – which chronicles the struggles of African Americans in the United States – Roye has been mindful of not letting previous projects or past successes inform too much of his approach to “Cleveland 20/20.”

“I’ve allowed Cleveland, for lack of a better analogy, to play its music to me, as opposed to bringing my own tune – instead of saying you’re going to dance to my drumbeat,” he says. “Every street has its own cadence.”

Sparking a conversation

As of early November, Roye made five visits to Northeast Ohio for “Cleveland 20/20,” each lasting at least a week. His approach involves traveling the same routes each day, observing daily goings-on, as well as planned field trips to specific buildings, organizations or neighborhoods.

“I usually just go there and look at what I see and make an authentic image from what is there,” he says. “My attitude with photography is never to photograph what’s not there or to sensationalize an image.”

One excursion took Roye to Kinsman Road on the city’s east side, where a group of African American boys pedaled toward him on their bicycles as he drove. His efforts to flag them down made them speed away because, he says, they feared he might be a police officer. He eventually caught up with them in a nearby cemetery, where he explained the project and they agreed to be photographed.

The resulting image portrayed youthful exuberance against a backdrop of ultimate demise. It’s striking. Viewers may be inclined to interpret the photo as a nod to a mainstream media narrative regarding young black men and boys and violence. Roye concedes the photo has a message but says it’s deeper than that – and he wants to make viewers work harder to receive it and reach a better understanding.

“My mom said you can take them to the trough but you can’t force them to drink. I’ll take you to the trough, but it would be such a disservice to the image if I just leave it at, ‘This is the history of black men in Cleveland.’ I could say they have no work, they have no resources, they have nowhere else to go. That, to me, would be the greater message. I’m just showing you the result of not having that.

“For me, an image is not an end-all-be-all,” he adds. “An image is a conversation, and let’s have the conversation – as opposed to just leaving it at, ‘Oh, this is what happens to black men in Cleveland.’”

He suggests the narrative is that the boys – as well as many other Clevelanders – are trying to forge their ways along a path fraught with obstacles.

“It’s easy to say, ‘OK, it’s about violence and this is where they end up,’” he says. “But I’ve yet to see one engineering school. I’ve yet to see one masonry school. I’ve yet to see one wood shop. In a place that has space – and a mayor – I’ve yet to see anything that says, ‘I care about you.’ So, yeah, the image is about these guys in a cemetery, but it’s about more. It’s about a conversation we can have to make sure they’re not in the cemetery.”

An outsider’s perspective

Roye might not search for themes, but they emerged as he worked on “Cleveland 20/20.” Emptiness – “not necessarily just buildings, but government responsibility” – is one example.

“There’s this huge void here,” he says. “Am I trying to photograph void? No. I’m trying to get at how people are living. How do people get by? What does that living look like? What is the culture of a neighborhood?”

But, undeniably, richness and fullness are also themes. Roye says he’s been warmly received by those he’s met, spoken to and photographed, adding that many Cleveland residents express a sense of pride in their respective neighborhoods.

Authentically documenting those qualities is both important to him and central to the vision of “Cleveland 20/20.” A trip to Slavic Village brought to life both the fullness of the neighborhoods and the cadence of the streets Roye identified.

“On (East) 61st (Street), Miss Debbie Eason was out on her steps, and there was this very loud Rosy, who is a car washer. Everything on that street was loud. A cello up the road was loud. Everybody was shouting,” he says. “You go down another street, somebody’s mowing his lawn. It’s quiet. Or, there’s nobody. On another street, there were kids riding their bicycles, wheelin’. So those are the different characteristics.”

He’s also been a student of Cleveland history. For example, in talking with members of St. John African Methodist Episcopal Church near East 40th Street and Central Avenue, he learned of Dorothy Dandridge, Ruby Dee and Langston Hughes.

“They went to school right around the corner – that’s not something I knew before,” he says. “So, it’s been important for me … to allow myself to listen to Cleveland, to listen to what was here, what is here, what people are trying to do and what people did.”

Roye realizes he won’t be the only one to learn from “Cleveland 20/20,” acknowledging some who see his work in the library exhibition may never have stepped foot in neighborhoods he visited. That’s an important audience for him, personally, to reach. Bridging that gap in connection and compassion could have a lasting impact.

“In seeking my voice, what was I going to photograph, this question was asked: Why are you doing this? It doesn’t change anything, so why are you pursuing photography with this aim in mind?” he says. “I think part of my ‘I’m going to prove photography can change the way people think’ birthed this idea that I can introduce Debbie Eason to you, and she’ll remind you of your aunt; the only difference is she has a different skin color. That’s my big hope for the project.”

‘Cleveland 20/20’ contributors

The more than 20 photographers taking part in “Cleveland 20/20” represent an array of talent. Many of them are prolific professionals: Tim Arai, Stephen Bivens, Bridget Caswell, Matthew Chasney, Hadley K Conner, Billy Delfs, Shelly Duncan, Aja Grant, Diana Hlywiak, Da’Shaunae Jackson, Adam Jaenke, Jef Janis, Dan Levin, Greg Martin, Christopher Mason, Ruddy Roye and Shari Wilkins.

An additional six photographers are students in Cleveland Print Room’s Teen Institute: Enahjae Beasley, Destanee Cruz, Maria Fallon, Felix Latimer, Gabrielle Murray and Owen Rodemann.

Curating “Cleveland 20/20” is Lisa Kurzner, an independent curator who has worked locally with the likes of Cleveland Museum of Art, moCa Cleveland and Transformer Station, and was curator for FRONT International in 2018. Her curatorial assistant is Haley Kedziora, former gallery director of ROY G BIV Gallery in Columbus.

An exhibition showcasing the photography of “Cleveland 20/20” will open on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Jan. 20, 2020, in Brett Hall at the library’s main branch in downtown Cleveland.