Upon second solo show at HEDGE Gallery, multidisciplinary artist Matthew Gallagher discusses how art can create itself

Story by Carlo Wolff

Matthew Gallagher ties the ends of an elastic band to screws securing a rectangular piece of paper, covers their fingers with paint, and twangs the rubber, triggering droplets that dry into art. This attaches paint to sound waves, Gallagher says. The hand is the bow, the band the slingshot, the twang the picture.

Variants of such liberation surround and engage this 28-year-old every day. The technique is purposeful but random – an example of Gallagher’s drive to scramble and enhance the senses.

R&D, a 2,000-square-foot studio in downtown Cleveland, is Gallagher’s laboratory. Its growths are diverse. Audio equipment – much of it vintage, like the dual-cassette recorder Gallagher uses to make copies of their original electronic music – occupies significant real estate. One corner is dedicated to a super magnet and other gear Gallagher needs to produce “magnetic field fossils,” disquieting, slurry-cured bursts of iron filings that look like turds from an asteroid. The place is awash in process, a concept Gallagher values as much as magic.

A native of suburban Boston, Gallagher has occupied this studio since 2014, a year after graduating from Oberlin College. Drawn to Oberlin by its music offerings, Gallagher – who identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them pronouns – turned toward art during their first painting class in 2011. There were limitations.

“I wasn’t really liking painting with a brush; it just wasn’t working out for me,” Gallagher says, adding painting with a brush was too traditional. “I needed to find another way to apply marks to a surface that was more engaging. For me, a big part of the problem was that the painting just wasn’t very high resolution. Every time you make a mark with a half-inch paint brush you’re making a half-inch mark. In the age of retina screens, you’re using tiny bits of information to make stuff.

“I had to create my own technology to make the images I wanted to make.”

Special mentors

In 2012, the second semester of junior year, Gallagher took a class called “The Nature of the Abstract,” taught by John Pearson, an artist and student of the influential German-American minimalist Josef Albers. What they learned was rigor: “We had to make 20 pieces of art per week, a really heavy workload,” Gallagher says. “You had to sign a waiver when you started taking the class that you wouldn’t fail your other classes while you were taking this class.

“That was a big thing with John: just consistently cranking stuff out. That’s how you make the discoveries that define your uniqueness as an artist, I think by a lot of trial and error.”

Pearson’s wife, the late Audra Skuodas, would visit class and was an inspiration herself.

“The amazing thing about Audra is she just did nothing but make art,” Gallagher says. She painted “wild, surreal portraits that looked like divine alien forms, but with really empathetic human elements. I loved the way she talked about art; she was really supportive of all the students.”

So was Pearson, who introduced Gallagher to the “Buddhist-mystic notion” of enso. In enso paintings, the act of creation – and the work itself – are portals, ways to transcend the self. What matters is what’s left behind.

“You meditate in front of a wet piece of silk, and at the end of your session, you in one motion draw a circle on the wet piece of silk and the circle sort of dissolves. You are not allowed to manipulate it at all; you have to just let the forces of nature dictate what happens to it.”

In one of these ensos, now on display at Gallagher’s second solo show at HEDGE Gallery in Cleveland, the artist drew a circle in black ink, then filled it with blue Sharpie so it looked solid. At that point, “it was really boring looking.” But in the process, “I go upstairs and pour a bunch of isopropyl alcohol on the floor and drop the paper into it and I leave. I go to bed. In the morning, when I wake up, instead of being a boring blue circle, I can see how capillary action has drawn the ink through the paper in different ways.”

In such pieces, and related, more complex “solvent paintings” based on elaborate grids, “the key is to soak them and then immediately leave. This might be a little superstitious, but I don’t hang around while they’re doing their thing.”

Do you think that would influence it? “Yeah,” they say. Do you believe in magic? “Of course. Magic is everywhere.”

As is faith. All you have to do is know how to tap into it.

The virtues of losing control

Fascinated by chromatography, this pigment connoisseur enjoys seeing ink travel in “solvent paintings,” which show “how things move around.”

“I think the most important discipline demonstrated here is letting go, just letting it compose itself,” Gallagher explains. “You can see the way it begins as this very rigid, sort of traditional, minimalist thing. Then I destroy it. It takes an entire day to draw this grid. … And destroying it, I think there’s some power to that. That requires a leap of faith.”

This approach extends to “Logarithm,” a larger acrylic painting of vertices, which seems to explode and implode at the same time. Such sound-based paintings also incorporate the rubber-band technique governing the smaller, sound wave works. “It’s a different perspective on that notion; instead of making a vibration, it’s making a percussive thwack,” Gallagher says.

Striking a balance

Art is Gallagher’s primary occupation, but music provides the steadiest income. Gallagher teaches private lessons in electronic music to a handful of students, maybe half of them regulars. Until recently, Gallagher hosted raves at R&D every two weeks. Still, smaller gatherings come together there. “I try to help people create things,” Gallagher says. “I just love helping other people with self-expression.”

And with community. Every summer since 2014, Gallagher has been involved with Voice of the Valley, an experimental, electronic-music festival near Morgantown, West Virginia. It’s “sort of like an intentional community” where people camp out. The nonprofit costs about $5,000 to run. It’s been postponed this year due to COVID-19.

To Gallagher, music may be more democratic, more economically accessible, than art. Where “Logarithm” may sell for $6,000, attending the whole Voice of the Valley festival costs $20.

Blinding us with science

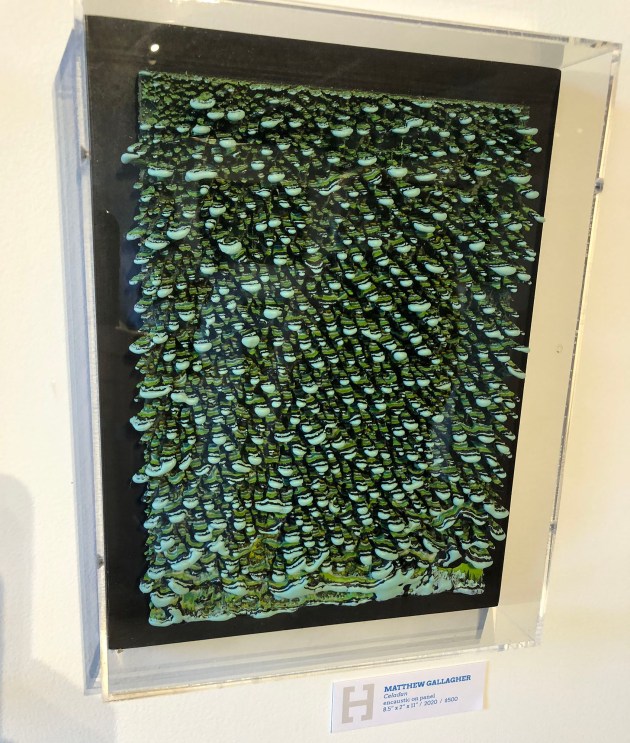

One Gallagher expression on display at HEDGE through Aug. 7 is a “growth mantra,” a work that looks three-dimensional. These mantras involve layering of wax and pigment “on top of each other over and over again” in “super-repetitive, muscle memory exercises,” says Gallagher. “My theory is that these repetitive processes yield organic forms much like cell division or geologic processes, or the way molecules are organized.”

They are palpable, alluring and disquieting. Like much other Gallagher work, they bespeak an affection for science – and a drive to get to the bottom of things.

“A big part of the way my art functions is for me to discover things about the material nature of our world, like trying to visualize sound with these paintings,” Gallagher says. “I want to see what that shit looks like. Sound is such a dynamic, interesting, vast thing, and we never see it; we’re sightless. That’s why we have other organs.”

“Matthew Gallagher makes artwork that reflects on the beauty and curiosities” experienced from nature, says Hilary Gent, HEDGE’s owner and operator.

“(Their) work is constantly evolving,” she says adding it allows for experimentation to influence many projects.

Gent recognizes the influence of Cleveland artists Pearson and Skuodas, but, she adds, Gallagher “is also venturing into new realms of art making,” creating work that is “so fascinating.”

“Gallagher’s thoughtful approach to using many different mediums and using them successfully makes (Gallagher’s) work special,” she says, adding that Gallagher combines the influence of sound, chemistry and mathematics to create art which puts their technique into a scientific category – very different from artists whose work stems from representation.

“I was terrible in physics and chemistry,” Gallagher says, “but I was always really interested in them. I was just having a hard time with the abstracted nature of them – the math and the calculations, and all of the nomenclature that you have to memorize.” Still, Gallagher was “fascinated by the organization of our environment, and the potential to make incredible conclusions about the nature of physics and chemistry. We all live in this world. I think we can all be equal participants in decoding it.”

If you go

WHAT: Matthew Gallagher’s “Research and Development”

WHEN: Through Aug. 7

WHERE: HEDGE Gallery, 1300 W. 78th St., Cleveland

HOURS: 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Wednesday and Thursday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Friday, weekends by appointment