Ensemble’s ‘Angels in America’ offers compelling storytelling

By Bob Abelman

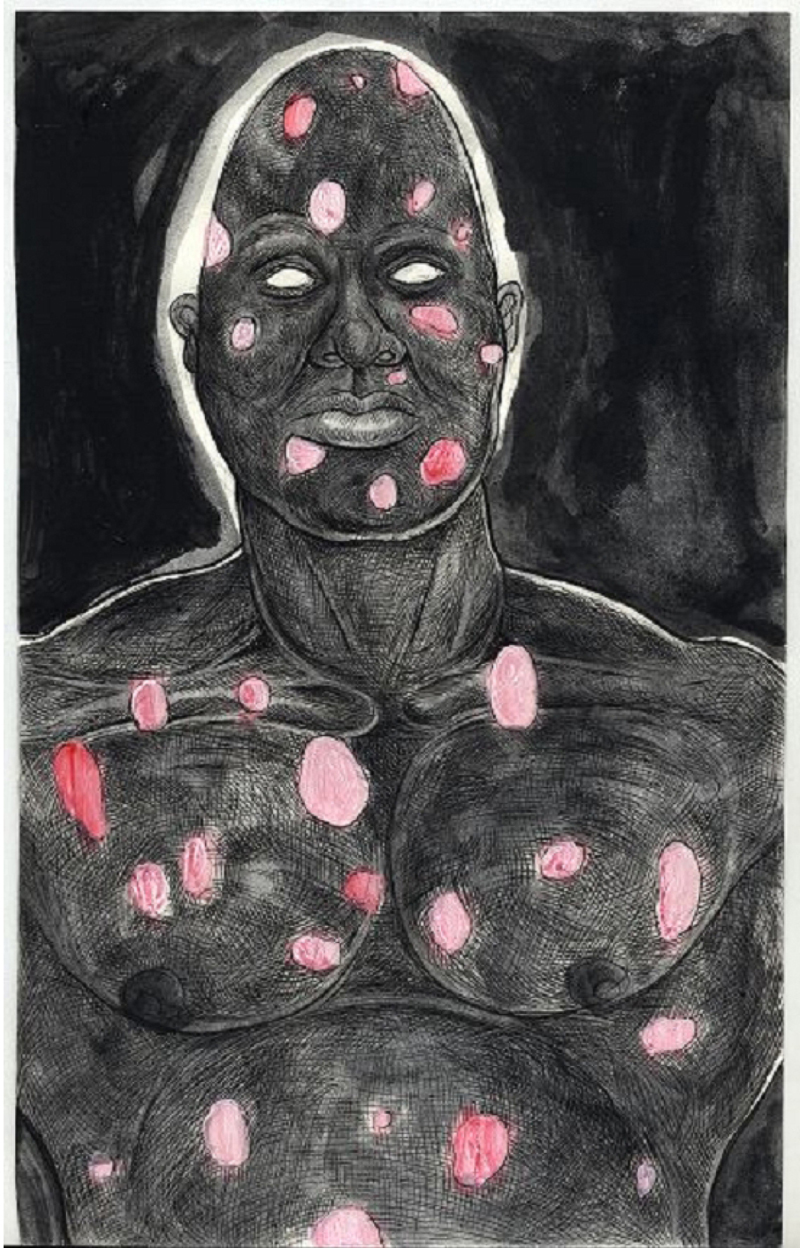

Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America” – which premiered in 1991 and is the winner of a Pulitzer for drama, a Tony for best play, and 11 Emmys – is set in the mid-1980s as AIDS ravages the nation and escalates the pre-existing discrimination aimed at gay men. Thirty-year-old New Yorker Prior Walter, the play’s key protagonist, is one of them, and this play takes us on his personal journey.

That is the short version of what is actually a landmark theatrical marathon; an audaciously ambitious work that is at once imaginative and unpretentious, uncompromising and affable, hard to watch and impossible to ignore.

The play, in its entirety, is told over two separate performances: “Part One: Millennium Approaches,” which is currently on stage at Ensemble Theatre under Celeste Cosentino’s direction, and “Part Two: Perestroika,” which will open there in April.

Collectively, the shows take longer than seven hours to perform, with Ensemble’s first installment clocking in at three hours and 20 minutes, during which we witness the parallel and occasionally overlapping stories of Prior’s illness and abandonment, a high-profile closeted prosecuting attorney facing his own demise, a closeted Mormon legal clerk coming to terms with his sexuality, and his Valium-addicted wife.

The play compares liberalism and conservatism during the Reagan years, offers a searing indictment of race relations in the U.S., and philosophizes about how the past shapes the present. It also forges an alliance between Judaism and homosexuality, reminding us – as if we needed reminding – how swiftly a fearful and divided society marginalizes, stigmatizes and ostracizes “others.”

Clearly, “Angels in America” demands a lot from its audience. It demands a lot from its cast members as well, who play multiple roles to demonstrate the elasticity of gender, social and cultural identities, as well as the implicitly theatrical nature of this work.

Fortunately, the characters that Kushner creates are so compelling, and his capacity to balance diatribes with dialogue, reality with drug- and disease-induced fantasy, and horror with humor is so engaging that the play keeps audiences ever-attentive, even during the occasional lapses in technical execution that blemished Ensemble’s opening-night production.

The show’s staging is similarly intriguing, for the script’s “Playwright’s Notes” calls for a “pared-down style of presentation” to make the show an “actor-driven event.”

Set designer Ian Hinz respectfully redefines “pared-down” by trading traditional scenery for projected imagery. The images offer artist-rendered and intermittently animated portraits of locations that are coupled with a single piece of furniture for each scene. The images appear on a rear screen that runs the length of the long and narrow performance space, which parts to reveal a deeper performance space and second screen, which parts to reveal a third. A period appropriate and thematically relevant soundtrack, including such tunes as Queen’s “Under Pressure,” plays between scenes.

Kushner’s play is enhanced by this treatment and still manages to be actor-driven. And the actors in this production serve up truly remarkable performances that showcase their characters’ distinctive brand of pain.

Scott Esposito’s boyish portrayal of Prior is immediately likable, increasingly sympathetic and eventually heroic as the indignity and hopelessness of the character’s AIDS-ridden and rapidly diminishing body plays out.

Craig Joseph, as Prior’s lover Louis, bears the full weight of his character’s anguish over abandoning Prior and offers an immensely moving, brutally honest performance.

So does Kelly Strand as Harper Pitt, the drug-addled and emotionally unstable wife of gay Mormon Joe Pitt who, in turn, is brilliantly portrayed by James Alexander Rankin. Harper’s chronic sorrow and all-encompassing melancholy is made palpable by Strand, and her ability to balance this with her character’s humorous delusions is dazzling.

As self-deceptive and loathsome lawyer Roy Cohn, Jeffrey Grover comes out of the gates slowly but becomes deliciously serpentine and increasingly repulsive as the play progresses.

Robert Hunter is a delight as the former drag queen turned nurse, Belize. He milks all the gallows humor out of his scenes with Prior and turns his hilarious debate about race with Joseph’s Louis into one of the highlights of this production.

Another is Derdriu Ring as Rabbi Isidor Chemelwitz, who opens the show by offering a eulogy that laments the loss of “the last of the Mohicans” of early Jewish immigrants who never fully integrated into American culture. Ring’s Yiddish, heavy Eastern European accent and impersonation of an elderly man are remarkable, as is her portrayal of Joe Pitt’s devoutly Mormon mother during a late-hour exchange with a homeless woman, played by Inés Joris.

Director Cosentino has put together a talented cast and crew to generate a very memorable production of a truly monumental play. Bring on Part Two.

“Angels in America,” Part One

WHERE: Ensemble Theatre, 2843 Washington Blvd., Cleveland Hts.

WHEN: Through Jan. 28

TICKETS & INFO: $12-$25, call216-321-2930 or visit ensembletheatrecle.org

Bob Abelman covers professional theater and cultural arts for the Cleveland Jewish News. Follow Bob at Facebook.com/BobAbelman3. 2017 AP Ohio Media Editors best columnist.

Originally published in the Cleveland Jewish News on January 8, 2018.

Lead image: Craig Joseph as Louis Ironson, from left, and Scott Esposito as Prior Walter. Photo / Celeste Cosentino