Fresh art, versatile apps bring depth to the first citywide AR show

By Carlo Wolff

Twelve African American artists who believe in Cleveland’s east side deploy augmented reality to highlight, enhance and comment on sites in East Cleveland, Glenville, Slavic Village, Kinsman, Buckeye and Central neighborhoods in “Crossroads: Still We Rise,” an ambitious exhibition by The Sculpture Center of Cleveland.

The purposefully immersive experience, driven by imaginative art, transformative apps and the city’s racial inequities, runs through Sept. 25, both at The Sculpture Center and at 12 outside sites. The artists featured are Lawrence Baker, Donald Black Jr., Marcus Brathwaite, Gwen Garth, Amanda King, Hilton Murray, Ed Parker, Shani Richards, Vince Robinson, Charmaine Spencer, Gina Washington and Gary Williams.

Robin Robinson, who curated “Crossroads: Still We Rise” and worked with Sculpture Center head Grace Chin on what Chin said is the first citywide AR exhibit, selected the artists for their ideology and professionalism. All the works involving the democratizing AR process are commissions.

The exhibition is designed to draw people to view economically wounded, historically resonant neighborhoods with a fresh eye and to foster dialogue about what can be done to celebrate and strengthen them. Its long-term purpose is to generate discussion of the potential of neighborhoods that for too long have effectively been left for dead.

“Still We Rise,” Robinson acknowledges, is profoundly political; it may be the start of something bigger, like a Black arts district, she suggests. At the minimum, she and Chin hope it is the first of many installations.

“We wanted to create a new program for The Sculpture Center where we were bringing art outdoors in a specific context,” says Chin, who became the center’s executive director in 2019. “I wanted content that was meaningful and that would create dialogue that reflected conversations going on in the rest of the country.”

App appeal

Chin also wanted to hitch new technology to new art.

Augmented reality in the gallery is hosted by RazorEdge, a Cleveland-based digital innovation firm. It uses iPad Pro cameras and an Apple app.

As RazorEdge’s Ocean Young recently demonstrated with “Listening Eye,” the African spirit vessel that Charmaine Spencer, a Cleveland sculptor, superimposes at the gates of Woodland Cemetery in Central, the Reality Composer app can make it spin and wobble, even get its clay bands to shake.

While Reality Composer creates the interactive AR experience, 4th Wall is the app used on site to publicly access the installations. The artists had to convert their works to JPEGs and PNGs, turning them over to Nancy Baker Cahill, who created the 4th Wall app, for AR use outdoors. There was a major learning curve, says Spencer.

“You have to consider when you’re making your piece what you want the viewer to see in virtual reality and how your piece is going to help that, not putting in anything that’s going to hinder what your vision is in virtual reality,” she says.

Because the technology was unfamiliar, the artists had to work with the technologists, making this project collaborative on yet another level, says Chin. “That was part of the goal because we wanted the artist to have the experience of working in a new medium.”

Rising agenda

Robinson, a community activist to the bone, has been living in Cleveland off and on for most of her life. She owns a home in Glenville. She’s tired of the incessant phone calls asking if she wants to sell her house (she doesn’t). She loves her neighborhood, dominated by East 105th Street. To the Philadelphia native, “Still We Rise” is more than an invitation to see the eastern core of this troubled city in a new light. It’s an opportunity to shine that light unforgettably bright.

“When I was a child, East 105th Street was like going downtown. My parents wouldn’t send Easter clothes with me because they knew my grandparents would just buy them on East 105th Street,” she recalls of her time there. “Anything else I may have needed, we could get right here.”

It had been about 20 years, after earning her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Temple University in Philadelphia, motherhood and a divorce that Robinson first moved to Cleveland around 1979. She then left for Fort Wayne, Ind., with her second husband around 1983. Even more years later, after a second divorce, Robinson returned to Glenville permanently in 2011.

“Coming back, it was just devastating to me,” she says. “I hadn’t seen the gradual progression like people who live here saw, I saw just the devastation.”

She eventually became executive director of Sankofa Fine Arts Plus, a nonprofit in the St. Clair neighborhood designed to empower African American artists. Sankofa is the name of a West African bird that can turn its head backwards. “The symbology is that you can move forward but always remember your past,” Robinson says.

Sankofa commissions murals and community engagement is one of its key tenets. So is the activism that led to “Our Lives Matter,” an AR overlay on the Cuyahoga County Courthouse unveiled through 4th Wall on Juneteenth 2020, shortly after George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis. A collaboration among the Sculpture Center, artists Robinson and Gary Williams, and Cahill’s app, it is the direct precursor of “Still We Rise.” The difference is scale.

“I’m passionate about the east side of Cleveland, and as an African American artist in Cleveland, I’m always fighting the system that funds art in Cleveland,” Robinson says. “I also am aware of the systematic racism of Cleveland between the west side and east side. I know where the red line is, and it’s in the middle of the Cuyahoga River.”

After many years away, she could see how foreclosures have damaged the east side far more than the west side.

“I’m always dealing with these communities on the east side in my professional capacity,” she adds. “I’m also on the west side as an artist and I work with these organizations as a teaching artist, so I know what’s happening there and not happening over here.”

The African connection

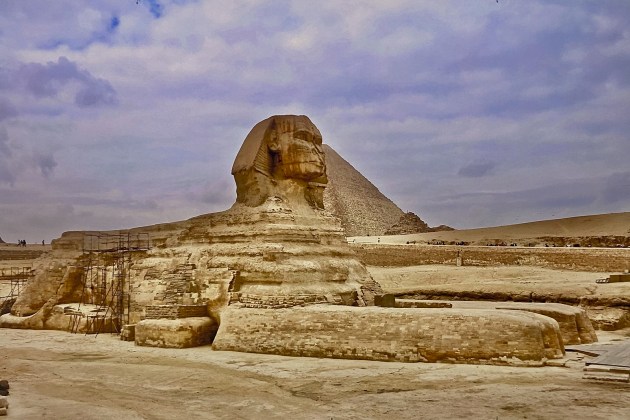

Vince Robinson, a photojournalist, musician and poet who has been covering the Cleveland scene – and more – for more than 40 years, chose East 99th Street and Buckeye Road for his “Still We Rise” installation. The place is empty, though there are signs it may have been a park, and a catch basin there suggests it’s a drainage site, perhaps under the jurisdiction of the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District. Visit that intersection, download the 4th Wall app to your smartphone and view Vince Robinson’s photo of the Great Sphinx of Giza.

Vince Robinson (no relation to Robin) traveled to Egypt and the Sudan in fall 2019 on a cultural tour. “It was transformative, it was phenomenal,” he says of the trip, which brought him “a greater level of understanding and appreciation of being African.”

Vince Robinson has added spiritual layers through his terrestrial and philosophical voyages. He also amassed indelible images like the one he captured at Giza, designed as “something to replace what has been destroyed or erased,” he says. “I’m also saving that space, in a sense, with something that is essentially African and relates to us there as well as here.”

Augmented reality “provides opportunities for artists in a very revolutionary way,” he says. “Back in the day, you could express yourself as an artist with graffiti, and when you did that, it left an indelible mark wherever you left your art, and in the process of providing your art you may have defaced something else.” There’s no defacing with AR, which leaves only a virtual trace.

“When you understand how augmented reality works and you’re connected with the right entities, you can put art anywhere,” Vince Robinson says. “It’s a different way of creating permanence – without intrusion.”

Black artists matter

Robin Robinson has been trying to establish an east side arts district for African American artists and residents in Glenville. Despite the occasional gallery “popping up in different places, we’re not cohesive enough to say, ‘This is an arts district,’” she says. “We’re kind of forced to be, you know, disassembled – and compete with each other. Why should we have to compete with each other?”

Is “Crossroads: Still We Rise” the seed of a Black artists collaborative?

“It’s not, really,” Robinson says carefully, hedging her denial in the next breath. “I have based a lot of my adult experiences on my favorite film, which oddly enough, is “Field of Dreams” – ‘If you build it, they will come.’ What I want to do with ‘Crossroads’ is have people see for themselves that these neighborhoods are not as forgettable and devastating, only able to be utilized as a resource for freeways, parks or whatever it is that money wants to be. These communities are not surplus.”

Chin says, “One of the goals of the exhibition is for the participants and viewers to take this information and say, ‘What should we do?’ Have people ever been to Central? East Cleveland? Not necessarily. Do people who have driven through Central know that once there were all these magnificent, four-story buildings? They’re gone. It is eye-opening because it’s a little bit shocking. Now, these are some of the poorest neighborhoods in Cleveland, in Ohio, in the country.”

Central used to be a thriving neighborhood, home to the storied Majestic Hotel, a Black visitor-only haven at East 55th Street and Central Avenue featuring great jazz. The artist Gwen Garth lived there for a time. Her AR work at that spot aims to resurrect the corner’s vitality.

“These communities already have their gems,” says Robin Robinson. “These neighborhoods already have something that they feel ownership for and they feel pride in. I just want other people to see that.”

On view

“Crossroads: Still We Rise” is on view through Sept. 25 at sites around Cleveland and at The Sculpture Center, 1834 E. 123rd St., Cleveland. To download a map of the locations, visit sculpturecenter.org/crossroads. To view the artwork at any of the locations, download the 4th Wall app on the Apple App Store or Google Play.