Less funny than it could be, Karamu’s ‘Day of Absence’ delivers heavy message

By Bob Abelman

The pre-vaudeville minstrel shows of the mid-19th century are considered the first theatrical art form that was distinctly American. They featured white entertainers in blackface makeup performing comedy and song-and-dance routines that caricaturized plantation slaves for white audiences.

God bless us.

As one would imagine, minstrel shows were particularly popular in the South before the Civil War, as a way of reinforcing widely held racist stereotypes and countering the abolitionist movement.

A century later, in 1965, playwright Douglas Turner Ward borrowed this art form to shed light on the state of racism that was inspiring the civil rights movement. In his satirical fantasy play “Day of Absence,” which served to launch the pioneering Negro Ensemble Company in New York City, Southern whites were caricaturized by black actors appearing in whiteface and behaving as broadly as their old minstrel show counterparts.

The play takes place in a rural town somewhere below the Mason-Dixon Line. On a random Tuesday, the white residents wake up to find that all the people of color have mysteriously disappeared. As shoes go unshined, white-only public restrooms go uncleaned and babies are left uncared-for, the municipality devolves into stunned disarray and then utter chaos. There’s talk of a police officer going crazy when he has no black men to assault. A Klu Klux Klan member expresses his disappointment that he wasn’t the one to drive “The Blacks” out of town and hopes that they will return so he can do so.

“Day of Absence” is a light entertainment with a heavy message, the kind that finds you laughing and feeling peculiar doing so. It is an important play – a gateway play – that would eventually give rise to works like George C. Wolfe’s 1986 take-no-prisoners satire “The Colored Museum,” which says the unthinkable and says it with uncompromising wit and leaves its audience an emotional wreck.

Karamu has resurrected Ward’s one-act for reasons best left to the audience’s sense of social awareness.

Nathan A. Lilly directs a solid production housed within a red, white and blue performance space cleverly designed by Prophet D. Seay to resemble a minstrel show stage. Inda Blatch-Geib has dressed the performers in clownishly clashing costuming that denotes the satire that drives this play.

The one problem with this production is that most of the members of this talented ensemble (Lachaka A. Askew, Jeannine Gaskin, Jailyn Sherell Harris, Robert Hunter, Maya T. Jones, Austin Black Sasser, Prophet D. Seay, Nate Summers and Sherrie Tolliver) fail to find a rural stereotype to call their own and make it sufficiently whitewashed. Only Hunter as the corrupt and incompetent Mayor, Seay as a variety of red necked yokels and bumpkins, and Jones playing an assortment of male and female locals get what the playwright was going after.

As a result, this play is less funny than it could be. More importantly, it makes white audience members like me less uncomfortable than we should be and has black audience members laughing at caricatures that more closely resemble those of the old blackface minstrelsy. For research, the cast should watch TV reruns of “The Dukes of Hazzard” and use Boss Hogg, his idiot son Cletus Hogg, and Sheriff Rosco for inspiration. Ernest T. Bass from “The Andy Griffith Show” is also up for grabs.

“Dying is easy,” said famed 1940s performer Edmund Gwenn on his deathbed. “Comedy is hard.” Satire in whiteface is even harder. CV

‘Day of Absence’ at Karamu

WHERE: Arena Theatre, 2355 E. 89th St., Cleveland

WHEN: Through Nov. 18

TICKETS & INFO: $25-$40, Call 216-795-7077 or visit karamuhouse.org

Bob Abelman covers professional theater and cultural arts for the Cleveland Jewish News. Follow Bob at Facebook.com/BobAbelman3 or visit cjn.org/Abelman. 2018 Ohio Media Editors best columnist.

Originally published in the Cleveland Jewish News on Nov. 15, 2018.

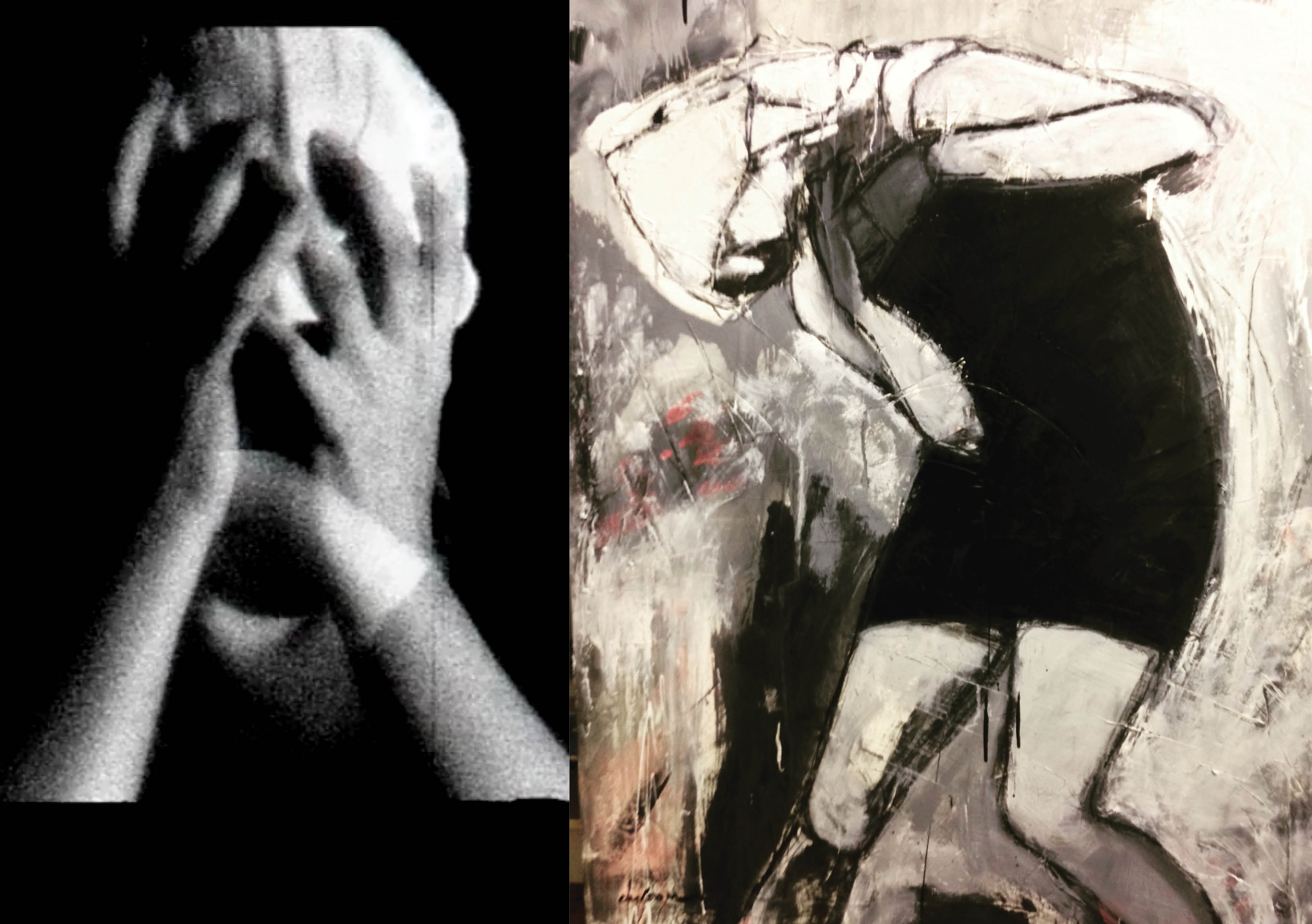

Lead image: Jailyn Sherell Harris and Robert Hunter | Photo / Vince Robinson