Performance arts audiences are aging nationwide, but Cleveland’s theater community is responding

By Bob Abelman

Most of us have read about, many of us have witnessed, and some of us are living proof of the aging of the performing arts audience.

The average age of those attending classical music performances, the ballet, jazz concerts and plays is increasing, according to the National Endowment for the Arts. This is not just because the median age of the general population is creeping up; it is the result of one generation of audience members not being adequately replaced by the next. This is particularly true of theater.

“Big Data” reports that the vast majority of subscribers to the Cleveland Play House and Great Lakes Theater were born between the mid-1920s and the mid-1940s, followed by members of the early baby boomer generation who were born between the mid-1940s and the mid-1950s. And the average age of attendees for the touring Broadway shows coming through Playhouse Square, according to the Broadway League, is 53 years old.

The average age of those attending classical music performances, the ballet, jazz concerts and plays is increasing, according to the National Endowment for the Arts. This is not just because the median age of the general population is creeping up; it is the result of one generation of audience members not being adequately replaced by the next. This is particularly true of theater.

When young, we tend to gravitate toward new artists and new art forms until our interests, income and evenings become more amenable to more traditional pursuits. But in recent years, fewer young people have been returning to the fold.

The way of ‘The Great White Way’

Broadway’s solution to securing its future, and by extension, the future of national tours of Broadway shows, is to rewrite some of the rules of the hit musical. Just like “Hair” did 50 years ago and “Rent” did 20 years ago, “Hamilton” – which takes the stage in Cleveland from July 17 to Aug. 26 at Playhouse Square’s State Theatre – infuses its storytelling with relevant themes, contemporary music and dance, and color-controversial casting to attract Generation Xers and millennials.

“We try to get children to color outside the lines.”Alison Garrigan, Talespinner Children’s Theatre

Raymond Bobgan, left, leads a discussion during Cleveland Public Theatre’s Entry Point 2018 Festival of New Work. Photo Steve Wagner / Cleveland Public Theatre

Many Broadway producers – particularly Disney Theatrical Productions – have set their sights even younger by transforming animated films into live stage musicals. Disney’s first venture was the 1993 adaptation of “Beauty and the Beast,” which had a 13-year run. Its success was eclipsed by “The Lion King,” which won six Tony Awards and has surpassed $1.4 billion at the box office and spawned 24 global productions in eight languages. Currently joining “The Lion King” on Sixth to Eighth avenues between 41st and 54th streets are “Aladdin” and “Frozen.”

Disney’s recent acquisition of 21st Century Fox is likely to produce more of the same on Broadway, considering Fox’s catalog is chock-full of properties ripe for stage adaptations for young audiences, including everything from classic Shirley Temple films to family-friendly titles like “Home Alone,” “Night at the Museum,” “The Chronicles of Narnia,” “Ice Age” and “The Diary of a Wimpy Kid.”

Changes on the home front

In recent years, local theaters in Northeast Ohio, including the Beck Center for the Arts in Lakewood, have also been targeting young adult audiences by adding off-kilter, Off-Broadway musicals like “Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson,” “Jerry Springer: The Opera” and “Ruthless” – which tend to feature young actors – to their more traditional schedules.

“Every theater has an obligation to its older subscriber base,” says Beck Center artistic director Scott Spence, “but it must also vary its product in order to invest in tomorrow’s audiences.”

Blank Canvas, at 78th Street Studios, alternates between modern classics, such as “Twelve Angry Men” and “Of Mice and Men,” and cultist musical comedies that include “Debbie Does Dallas,” “Psycho Beach Party” and “The Texas Chainsaw Musical.”

This is part of artistic director Patrick Ciamacco’s master plan to lure younger audiences to the theater via offbeat offerings and then strategically introduce them to the classics.

“The audience isn’t graying – it’s always been gray.” Teresa Eyring, Theatre Communications

Other theaters offer student discount tickets in an effort to reach teens and 20-somethings with less disposable income than older subscribers. The first Sunday of every Dobama Theatre and Ensemble Theatre production in Cleveland Heights, for instance, is a “Pay-as-You-Can” performance, and Great Lakes Theater in downtown Cleveland introduces more than 15,000 students to theater each year through its discounted “All Student Matinee” performance dates.

Cleveland Public Theatre in Cleveland’s Detroit-Shoreway neighborhood lures in young locals with “Free Beer Fridays,” strategic social media outreach and its innovative and creative risk-taking enterprises, like Entry Point and its annual fundraiser, Pandemonium.

Entry Point is a platform for young artists to develop their work in the early stages of creation, and then share that work with young audiences as staged readings, in short excerpts, and through guest panel discussions.

Playhouse Square and South Euclid’s Mercury Theater open their doors to even younger audiences with their Children’s Theater Series and “My First Musical” program, respectively.

Points for participation

All this may get younger derrieres in the seats for isolated events, but to keep them there for the long haul, perhaps it is necessary to not only introduce the next generation to the performing arts but establish a life-long appreciation of and passion for them.

“I think Entry Point is one of our best audience experiences, as well as a platform for new play development – and those two things don’t normally go hand in hand. It’s a really fun night. It’s a party.” Raymond Bobgan, Cleveland Public Theatre

Enter Talespinner Children’s Theatre, which began operations in 2011. This Cleveland-based company develops and produces original, one-hour professional productions that challenge young children’s imaginations and are geared specifically for their attention spans and interests.

“We engage children as creatively as possible, using all their senses,” says Alison Garrigan, the company’s executive artistic director. “And, we make sure that there is something for every child of every age level and the adults who bring them. If adults aren’t attending or if they aren’t entertained, their children will certainly pick up on this.”

Talespinner strives to give children ownership of the show they see and make each performance a unique and personal experience.

“So, we ask children in the audience to provide sound effects or invite them to help a character solve a problem, to talk to the actors, and become a part of the story and the storytelling,” says Garrigan.

Finding financial support for this kind of work is an uphill climb. Youth theaters tend to receive less funding from government agencies than adult theaters, according to a recent report in American Theatre magazine. Only 19 of the 277 companies that received NEA theater funding last year were youth theater-focused institutions. Of the 506 organizations that received Shubert Foundation Grants last year, fewer than 40 offered youth theater.

What theater can and should be

Coloring outside the lines will eventually lend itself to children having a better understanding of what theater is and what it can do, and it will establish expectations and provide standards with which to evaluate how well it is done.

It will also require theaters to offer fare that accommodates the next generation’s conception of what theater can be and should be.

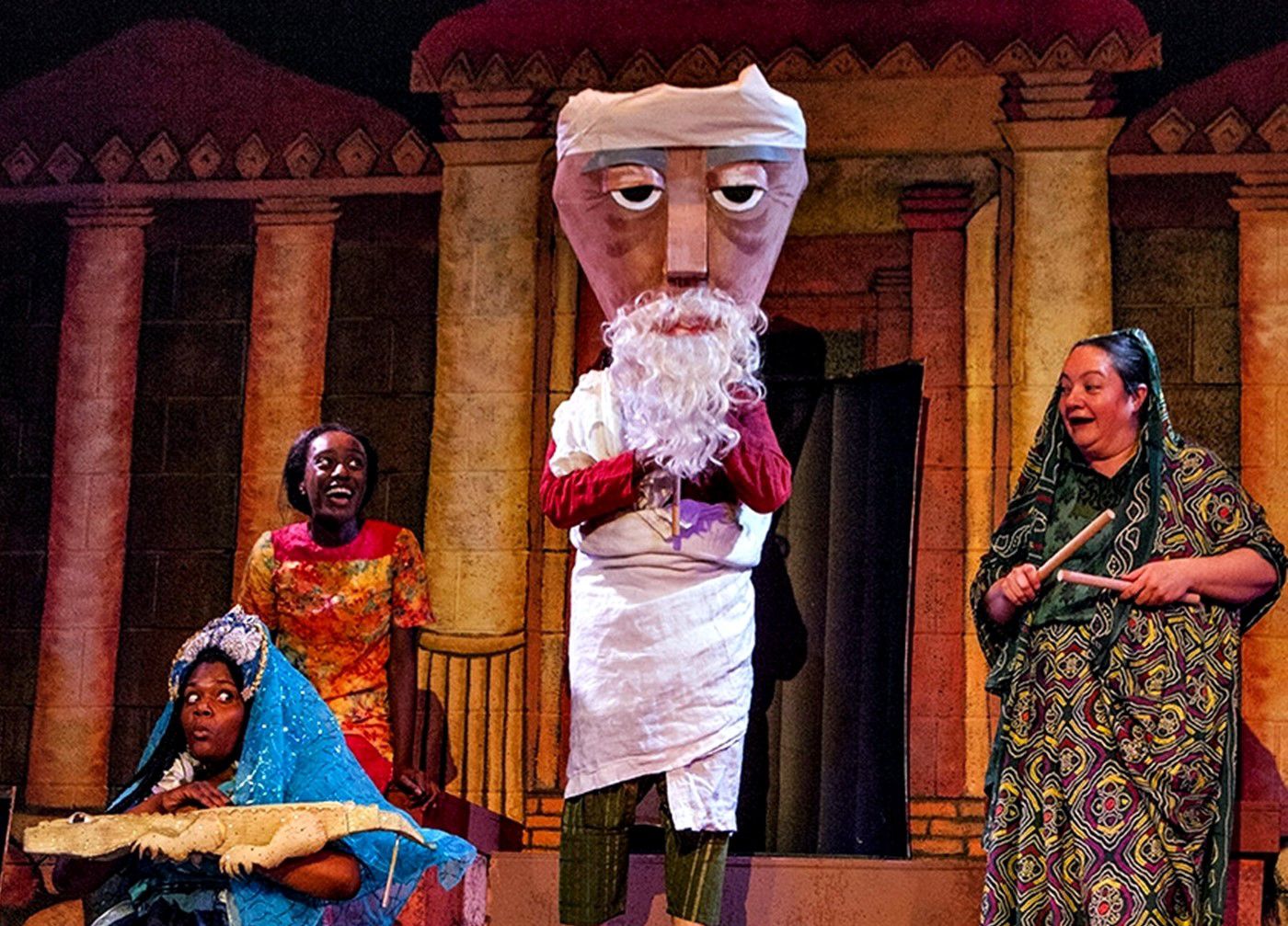

From left, Wesley Allen, Davis Aguila, Marina Gordon and Emily Jane Zart performing in Talespinner Children’s Theatre’s “The Rainbow Serpent (A Tale of Aboriginal Australia).” Photo Steve Wagner / Talespinner Children’s Theatre

Jordan Tannahill – author of the recently released manifesto “Theatre of the Unimpressed” (Coach House Books) –

argues it’s the “theatrical realism that has become so ubiquitous in regional theaters that is keeping young people away.”

In addition to their providing traditional and classic works, he proposes that theaters dismantle the status quo of artistic thought by offering a more appropriate form of storytelling for those “raised on the fragmented narratives of YouTube and Vine loops and the participant-observation of video games.”

In Cleveland, some already are.

“We create immersive encounters that transform the way people experience the world,” says Jeremy Paul, artistic director of Maelstrom Collaborative Arts. “Combining diverse genres, disciplines and media, we explore new forms of performance and collaboration.”

Once a nomadic company known as Theater Ninjas and referred to as the “food truck of Cleveland theater,” Maelstrom Collaborative Arts has put down roots in a storefront in the Detroit-Shoreway neighborhood and is entering a new phase of existence.

“As Broadway musicals go, ‘Beauty and the Beast’ belongs right up there with the Empire State Building, FAO Schwarz and the Circle Line boat tours. It is hardly a triumph of art, but (it’s) a whale of a tourist attraction.” David Richards, New York Times theater critic

“Our upcoming work is putting an emphasis on performance at the expense of ‘theater,’” Paul says. “We are pushing harder into multi-disciplinary experiences and work that requires the audience to play an active role in unspooling the narrative threads. Young audiences want to feel engaged by something unique, that they got to see something special. The performers and the audience need to live in a shared moment.”

If these initiatives don’t help attract younger audiences to the theater, perhaps nothing will. CV