Lane Cooper distorts everyday imagery, transforming the ubiquitous into the experiential

Story and photography by Michael C. Butz

A core facet of Lane Cooper’s artistic viewpoint came into focus 10 years ago during one of her darkest hours, sitting bedside watching her mother succumb to a severe stroke brought about by complications from cancer.

“It took a little while for her to die,” Cooper says. “She was in hospice, and there were all these other folks around, and they all seemed to be having these very modified experiences of reality. I knew what my mother was experiencing was very different from what I was experiencing even though we were in the same room at the same time.”

Playing with perception is a significant element of Cooper’s art. Her artistic repertoire is wide-ranging, but her most prominent pieces are layered paintings defined by the horizontal banding she employs; the result is experiences that shift depending on one’s perspective, and images that evade full grasp. What may seem clear when viewed from afar breaks up as one approaches for a closer look.

“Pop Life – MTM” by Lane Cooper, acrylic on canvas, 12 x 12 inches, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist.

Further, the banding serves as a sort of signal interference that interrupts a viewer’s relationship with the recognizable.

Cooper regularly culls subjects from pop culture and the entertainment industry. A piece she was working on in

mid-October in her Waterloo Arts District studio depicts the house from “The Waltons” TV series, which came on the heels of a painting based on Mary Tyler Moore’s house. Both are part of the “Dream House” series she’s building, and both portray only fractions of their familiar forms.

Dreamlike qualities are intrinsic to Cooper’s art. She says those moments between wakefulness and sleep, when reality bleeds into fantasy, inform her work.

“I kind of think we’re all always on that spectrum,” she says. “Sometimes we’re more tuned in to the physical world than others, but it’s always being filtered through our perception in a way that changes it significantly.”

Achieving that visual experience – evoking a hypnagogic state of consciousness through material and palette – is Cooper’s endeavor.

Accidental art education

Cooper applies with precision strips of masking tape to a piece she’s working on that depicts the house in “The Waltons.”

Cooper grew up in Hamilton, Ala., in the northwest corner of the state.

“Elvis’ baby-sitter was from my hometown,” she says, referring to Elvis Presley, whose hometown of Tupelo is about 50 miles west of Hamilton.

That isn’t even her best Elvis story. Cooper’s father and his best friend had a few drinks one night decades ago and successfully placed a long-distance call to Presley’s U.S. Army base in Germany.

“Because they had a Southern accent and they had the right area code, (the Army) put Elvis on the phone,” Cooper explains, “and my dad, of course, hung up when Elvis said hello because they didn’t expect him to answer.”

Her father, J.E. Cooper, was a pharmacist, and her mother, Katie, worked at the store in which the pharmacy was located. Both came from large, poor, rural families consisting of generations of subsistence farmers, loggers, railroad workers and elementary school teachers.

Katie Cooper provided her daughter artistic inspiration, allowing her to play with paints at home when she was as young as 3.

“I decided when I was a little kid that I wanted to be an artist,” Cooper says. “Most folks go through phases of wanting to be something else. I have never wanted to be anything else. And when I have gone through other ambitions, which I still have, it’s always, like, artist/writer – there’s always a ‘slash,’ and artist is always first.”

However, J.E. Cooper wasn’t supportive of his daughter’s desire to pursue painting.

“There weren’t people going to college on my mother’s side of the family, and on my dad’s side of the family, if people went to college, it was for ‘practical’ professions,” she says. “He told me he wasn’t going to pay for my college if I went into art. So, I got a job, and my mother gave me money under the table. … The tuition got paid mostly by mother, and I paid for everything else.”

Cooper graduated with a painting degree in 1984 from the University of North Alabama, in Florence, but along the way, her father wasn’t the only one who questioned or was confused by her career choice.

“Some of the people who taught me – my painting professor, in particular, who was a brilliant painter and a sweet, beautiful man – he told me that he assumed I was going to get married and have a bunch of kids, and that was why I was getting an art degree,” she says. “So, nobody was mentoring me at that point, in my early 20s, and nobody was giving me a leg up.”

Cooper says where she grew up, many felt painting was something one did on Sundays, outside of holding down a “real job.”

“That was everybody else’s perception. I had no perception,” she admits. “In fact, my only model for what an artist’s life looked life were my professors, and I’m certain that’s one of the reasons I ended up teaching – because I didn’t know how else you went about it.”

Dual devotion

- “It’s A Wonderful Life – Granville” by Lane Cooper, acrylic on birch panel, 20 x 20 inches, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist.

- “It’s a Wonderful Life – Valentino” by Lane Cooper, acrylic on canvas, 12 x 12 inches, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist.

Cooper earned a master’s degree in art history in 1989 from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and a Master of Fine Arts degree in painting in 1998 from the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa.

“I started teaching when I was working on my master’s in art history,” she says. “It was a lot of fun. Folks who are in school, and they’re in an art class, or an art history class, usually, they’re interested in something. I love people who are interested in things.”

In 2001, she came to Northeast Ohio and began teaching at the Cleveland Institute of Art, where she’s currently chair of the painting department.

Christopher Whittey, senior vice president of faculty affairs and chief academic officer at CIA, speaks highly of her teaching.

“She has a rare combination of being a very nurturing and caring individual, yet she can be pretty tough and demanding with the students,” he says. “When I’ve seen her in critiques with students, she really holds them accountable.”

“They think you’re the devil right up until they graduate, especially during their last semester,” Cooper says, smiling – and acknowledging the dynamic.

“They don’t all think that, but a lot of them think, ‘Oh, you’re just torturing me,’” she says. “And then they graduate, and it’s like a light flicks on for at least some of them. Then they have this great feeling of accomplishment and they have this work to be proud of. And to see them stand up there and answer questions very seriously about their work, it’s amazing.”

What’s also distinctive about Cooper, Whittey adds, is the devotion she brings to her dual roles as artist and educator.

“This is the ninth school I’ve been at” as a student or as faculty, he says. “It’s relatively rare, in my experience, outside of CIA, that you see someone who’s so committed to both of those roles.”

Strong female leads

Cooper is also committed to featuring prominent females in her work. Chief among them is the late Mary Tyler Moore. Not only has Cooper depicted the iconic actress’ home for her “Dream Houses” series, she’s painted portraits of the star herself – and a People Magazine cover of Moore hangs in her studio.

“When I was growing up, Mary Tyler Moore as Mary Richards, I was a little kid, but I thought she was the shit,” Cooper says. “She was so cool and so smart and independent. I wanted to be like her.”

Someone Cooper is considering for her next “Dream Houses” entry is the fictional Peggy Fair, loyal secretary to TV sleuth Joe Mannix on “Mannix.” Played by Gail Fisher, Peggy was a trailblazing character: an African-American single mother – two rarities for late 1960’s TV – who often kept things together at the title character’s detective agency.

“I do have male figures in my paintings sometimes, but I think I’m really interested in making women present,” she says. “I really like the idea that women get a starring role.”

The strongest female lead of them all, however, is likely the artist herself.

Cooper isn’t one to dwell on her “tale of woe,” as she calls it, but the 54-year-old has endured many distressing losses. Cancer, or its aftereffects, has killed three immediate family members: her mother, father, and only sibling, Kathy.

When she was 33, Cooper was diagnosed with thyroid cancer.

“I was very sick during my 30s,” she says. “I was in and out of the hospital a lot of that time. I went to grad school, I got my MFA, and I kept working and teaching, but I had a lot of surgeries during that time.”

Battling the disease set her back in some ways, she acknowledges. It not only slowed her career as she was transitioning from being a student to a young professional, it took a toll on her emotions and psyche.

“I feel like I lost that sense of immortality that younger people tend to have,” she says. “I think you usually don’t get to the mindset I was in during my early 30s until you’re in your 60s or 70s.”

Today, Cooper feels fit – younger than her age because, she jokes, “I felt so shitty when I was in my 30s!” – but her fight against cancer is ongoing. Every time she forgets she’s mortal, she says, something comes along to remind her otherwise – but those experiences also remind her to keep her eye on what she feels is important.

“I write and I paint and I teach, and I think I go about those things in the way that I do because I know life is short, and I know there’s very little to be gained by having it not satisfy me,” she says. “I want my work to carry something that I feel is true, that I feel is important. Otherwise, I don’t want to do it. If I’m just making paintings to decorate somebody’s wall, I’m not interested in that. It’s a waste of my time.”

Profound experiences

Palette is important to Cooper. She sometimes mines source images but she’s also often inspired by the Lake Erie sunset.

Earlier this year, Cooper – and much of Cleveland’s creative community – lost close friend and CIA colleague Dan Tranberg to heart disease.

Cooper admits she’s having a difficult time accepting Tranberg’s death, but as she applies bands of masking tape to “The Waltons” house in her studio, she fondly recounts the ways in which he helped improve her art, from suggesting she mine her source images for a painting’s palette to helping make the creative connection between her banding method and the breaking-up effect of digital images.

“Dan always gave himself,” she says. “He didn’t hold back, and he didn’t hesitate to give. … He wanted your work to be better, and he would give you stuff to help make your work better.”

Today, Cooper’s work is unmistakable and singular. Pieces from her “It’s a Wonderful Life” series, like “Valentino,” “Martini” and “Granville,” are visually stunning – and both challenge and invite viewers to see between her intricately placed lines.

CIA’s Whittey describes it as of its moment – significant at a time when people consume more images in a week than they saw in a lifetime during the Renaissance and earlier.

“Critically, the strategy she deploys fragments and disturbs the image through the horizontal banding across the surfaces of her paintings. This speaks to the shattering, fragmentation and ‘white noise’ of image production and consumption in the contemporary world,” Whittey says. “It seems to me, then, Cooper’s work ironically suggests that image recognition and comprehension become more challenging precisely as the images become more numerous, more ubiquitous, more everyday-ish. The overly familiar, one could say, becomes ‘defamiliarized.’”

Cooper wants her art to achieve an effect similar to that of revered Cleveland artist Julian Stanczak. She’s quick to clarify she’s not comparing her paintings to his, but her goal is to provide viewers of her art the same “profound experience” they get when viewing the late Stanczak’s work.

“When you stand in front of one of his paintings, and it’s one of his particularly amazing paintings, there’s a buzz that goes off in your head with the colors,” she says. “You want the color to click, you want the physical material sensibility of the work to be right there. Visually, I want my work to work on a lot of different levels, so, when you get up close to it, I want it to fall apart. I want you to have that Julian Stanczak experience.”

Cooper not only creates that buzz, she’s on her own frequency, producing thought-provoking art that engages and captivates. CV

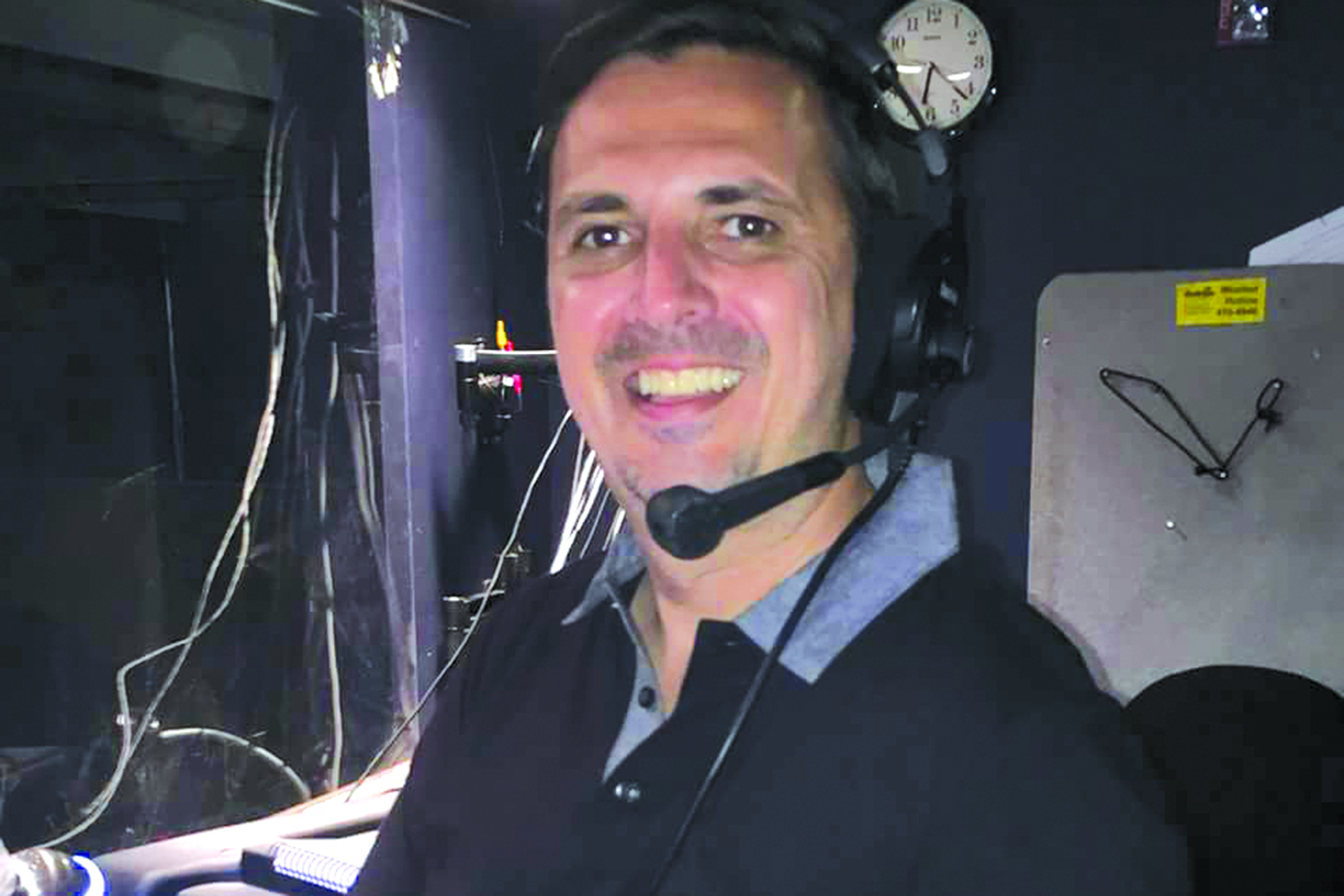

Lead image: Lane Cooper says she’s always working on multiple works of art at any given time, as evidenced by the contents of her studio in Cleveland’s Waterloo Arts District.