‘Massacre’ is both the title of and commentary on con-con’s production

By Bob Abelman

At the core of José Rivera’s “Massacre (Sing to Your Children),” first staged in 2007 at the Goodman Theater in Chicago and currently in production by convergence-continuum, is an outlandish tale about oppression.

The oppressor is a fellow named Joe, whose powers include the mind control of children, the ability to look into the souls of adults, and making infertile the land and the women of the small town of Grandville. For five years, he has engaged in psychological torture, rampant rape and the killing of those who do not abide by his strict and strictly enforced curfews.

It is never clear whether Joe’s reign of terror represents a political dictatorship, a religious theocracy or the innate evil in the human animal – all of which are even-money bets considering Rivera’s other works (“Marisol,” “The Motorcycle Diaries”) and the themes they embrace. What is clear is that Joe’s hunger cannot be satiated, his charisma cannot be quenched, and his evil cannot be extinguished.

We know this because, at the start of the play, the seven townspeople brave enough to revolt against and brutally butcher Joe return, bloody and euphoric, to their leader’s humble apartment to revel in their victory and make plans for the future, only to have Joe – still alive, angry and vindictive – come a-knocking by intermission.

Some of the seven are willing to give the killing of Joe another go but after turning on each other and forsaking their leader in frustration, most regret their primitive acts of violence, repress their oppression by finding comfort in it, and return to their homes.

The play’s ambiguity – about what Joe represents, about what the revolt against him means, and about what the revolt’s failure signifies – is never addressed or resolved over the course of the evening, which is infuriating. This play is an allegory for something, but what is anyone’s guess.

The ambiguity is not nearly as infuriating as Rivera’s means of presenting it. Much of the play’s dialogue employs stilted, pretentious, heightened language that is as uncharacteristic of the ordinary folks who speak it as it is foreign to the kind of story in which they reside.

Imagine John Gielgud or Laurence Olivier reading and paraphrasing aloud a Steven King novel and you’ll get a sense of this highly stylized piece of storytelling.

While some performers in this production (Hillary Wheelock, Beau Reinker and Lucy Bredeson-Smith) have created distinctive characters who manage to speak this dialogue with a sense of authenticity and urgency, others (Wesley Allen, Kelsey Rubenking and Brian Westerley) only come close while a few (Dennis Burby and Jamal Davidson) never seem comfortable in the skin or with the words they’ve been assigned.

Other productions of this play have attempted to bypass its ample ambiguity and off-set its off-putting pretentiousness by throwing theatricality at it in the form of visceral intensity – an amplified soundtrack, an infusion of Latin-American magical realism, and gallons of gore. Some have set the play in an abandoned slaughterhouse, costumed the seven vigilantes in grotesque animal masks, and armed them with pick-axes and tire irons instead of weapons fashioned from household tools used for dicing and slicing.

But con-con’s production, under Clyde Simon’s direction, goes to the other extreme.

The setting is a low-budget rendering of a low-rent apartment. The staging is stark and comparatively realistic. The gore is limited to stains on clothes and dried blood sparingly smeared on hands and faces.

Such minimalism works well because it allows the powerful poetry that Rivera scatters throughout the script to be delivered without distraction. But it calls attention to the play’s many imperfections as well.

It also turns the play’s drama into unfortunate melodrama on the occasions when Simon chooses to step up the production values. This happens when actors about to soliloquize step into the isolating illumination that lighting designer Cory Molner has waiting for them and when sound designer Beau Reinker’s gentle underscoring swells to signal a mood shift.

It’s admirable that Simon and company have taken on a play with such a high degree of difficulty, particularly since few productions have been able to turn it into something worthwhile. But we need to add con-con’s production to that list. CV

On Stage

WHERE: Liminis Theatre, 2438 Scranton Rd., Tremont

WHEN: Through June 10

TICKETS & INFO: $10 – $20. Call 216-687-0074 or visit convergence-continuum.org

Bob Abelman covers professional theater and cultural arts for the Cleveland Jewish News. Follow Bob at Facebook.com/BobAbelman.3.

Originally published in the Cleveland Jewish News on May 21, 2017.

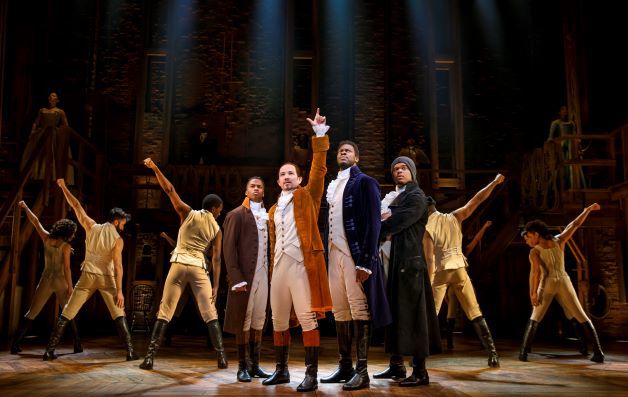

Lead image: Back from left, Dennis Burby as Hector, Wesley Allen as Panama, and Beau Reinker as Eliseo. Front from left, Kelsey Rubenking as Janis, Jamal Davidson as Eric, and Hillary Wheelock as Lila. Photo | Cory Molner