The photographer and owner of Foothill Galleries of the Photo-Succession talks about “Moonlight in the Gates: 150 Years of Lake View Cemetery in a New Reflective Light.” The exhibition opens from 5 to 8 p.m. July 23 at the Cleveland Heights gallery and will remain on view through Aug. 31. Related outdoor works will be on display throughout Lake View Cemetery from July 22 through fall 2020.

What can visitors look forward to from “Moonlight in the Gates: 150 Years of Lake View Cemetery in a New Reflective Light”?

Simply put, the intrigue of historic Lake View Cemetery by moonlight. Really, here’s the recipe: Take a 200-acre, 150-year-old unlit cemetery. Put an artist inside its locked gates at night by moonlight in all different seasons and conditions and you come up with a wholly new, creative interpretation of a rather well-known place. “Moonlight in the Gates” is an unfamiliar view of the familiar. Many people in Cleveland know Lake View Cemetery — its gorgeous rolling acres, its famous gravesites and monuments, and its personal spaces where family members are buried — but few people have seen it like I have.

In addition to what’s on view at your gallery, there’s a component at Lake View Cemetery itself. Will you elaborate on that?

When I began this project, I was doing it for personal, artistic reasons. By the second full moon visit, I realized this was something special, and I shared some images with (president and CEO) Kathy Goss at Lake View. We decided these images should become a unique component of the cemetery’s 150th anniversary celebrations in 2019-20. So, we worked out a way to display large prints outside in various locations throughout the cemetery for a year beginning this week (July 22). Now, visitors will have a chance to see my moonlight images in situ, so to speak — in the location where they were made.

What inspired this artistic pursuit and how long had it been in the works?

As a child, my father took my siblings and me to Lake View to visit the gravesite of his father and mother. Our family connection grew when my father-in-law was buried there in 2004. My wife and I walked there regularly with our children at different times of year. I began to wonder what this massive, eclectically ornamented garden cemetery would look like in moonlight. Would it be scary, captivating, alive, quiet, inspiring? I’ve long loved great works of art made by the inspiration of the night and the moon (particularly photographs by Edward Steichen and Bill Brandt, paintings by Ryder and Blakelock, Greek vase painters — pretty much every artist lassos the moon at some point). After our younger son, Josh, passed away and his grave was placed next to his grandfather’s, our visits to Lake View took on a whole new meaning. Again, too, when my father passed away in 2015. My son Josh knew about my interest in photographing the cemetery at night — he thought I was crazy. I just couldn’t let go of the idea. After some cajoling and persistence, I was given the key to the gates on Jan. 2, 2018.

What was it like to spend nights locked inside Lake View Cemetery?

Well, let’s see. I’d lock those massive gates behind me then head into 200 acres of unlit gravestones, monuments and crypts, massive trees, and sloping hillsides. There was darkness infused with strange noises, creaking branches, swaying shadows, owls whizzing by — and not a person in site. In other words, completely and totally alluring. I watched the moon highlight the back of the Haserot Angel, and then from the Garfield Memorial porch, I watched it set into the Cleveland skyline. I experienced a midnight snowstorm that blanketed the west side of every monument and tree. I listened to coyotes remove the night’s silence with their otherworldly chorus. You know, Edward Hopper once said that all he wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house. I was able to photograph moonlight on the side of Wade Chapel. Priceless.

Was there a particular night or particular scenario that stands out above the rest and was captured in one of your photos? If so, what was it?

The second full moon in January beckoned on a cold, clear night. When I made my way to the upper portion of the cemetery, I looked out beyond the Wade Monument in Section 3 and saw what appeared to be a rainbow in the sky, at midnight! I was dumbfounded. Sure enough, there in the southwestern sky was a spectrum of colors hovering above the trees in front of a midnight blue sky. Was this the northern lights in Cleveland? I think I let out a profanity of joy. Actually, as I stared at this meteorological phenomenon, it began to disappear. I literally was holding two tripods and two cameras at my sides as this spectral evening cloud of color was vanishing. Fortunately, I got my head together and set up the cameras. This was not the most moving artistic experience in the cemetery but it was the most phenomenal, otherworldly one. I thanked Josh for it. The next day, I contacted the Cleveland Museum of Natural History for an explanation. We never did resolve exactly what it was I saw that night. CV

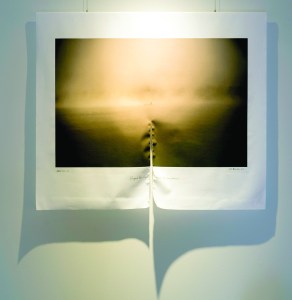

Lead image: “Black Moon Light 02-28-18 03:55 50°” ©Michael Weil 2019